By Erik Sherman

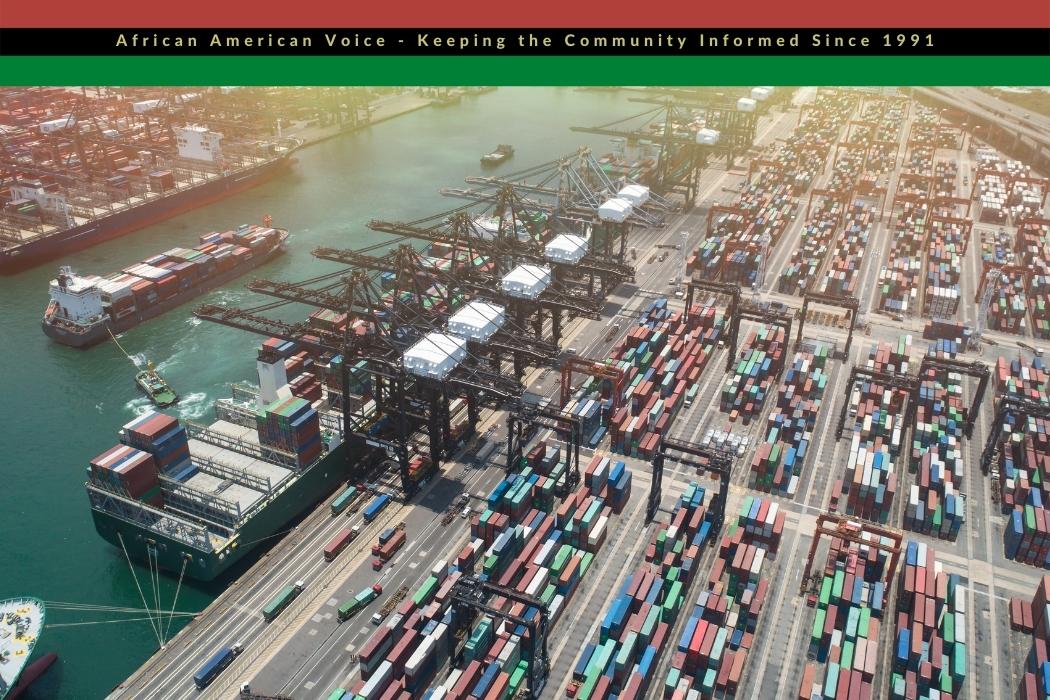

If you’re in business, any of these may sound familiar at this point. You can’t get large plastic cups for iced drinks. Building supplies. Pet food. Car parts. Cars. And lord knows what else. The supply chain blues.

GMH Communities, which builds and operates student housing and hears that if it needs appliances for 400 units, that could take six to eight months. “It’s a nightmare,” GMH president Gary Holloway says of the shortages. “It was everything from appliances to steel to more.”

“Companies are saying, ‘My product is being stopped, not because of some critical thing, but because of a plastic holding device for a custom box on an automated line I have,’” says Ethan Karp, CEO and president of MAGNET, a manufacturing advocacy and growth network in northeast Ohio. “I designed my line to work with this piece. It will take time to find another vendor, to get the molds made.”

Even as things supposedly are easing up, the improvement is in the symptoms. Three classes of causes remain to rise up at the next disruptive trigger, because Covid-19 was a trigger, not an absolute cause.

Poorly executed supply chain management

Many have pointed to back-ups at jammed ports, a lack of truck drivers, labor shortages, Covid-19, and the saying that “it’s a lot easier to go from 60 to 0 miles per hour than from 0 to 60.” All of which may be true.

But there’s a bigger cloud over supply chains and logistics. For decades, such strategies as lean and just-in-time supply chains have been popular, reducing the amount of on-hand and in-transit inventory through greater efficiency in production and distribution, freeing up money to invest in other areas of a business.

At the same time, experts in logistics have warned that there are good and bad ways of using these tools. Too many corporations take the latter approach.

“Just in time inventory works really, really well if you believe [your] Tier-1, Tier-2 suppliers are ironclad,” says Aaron Alpeter, founder and principal of supply chain and operations firm Izba Consulting. To ensure that they are working as they should, a business needs to monitor their supply chain. “You don’t have to wait until something bad happens. You should be partnering with your suppliers, knowing what’s going on in their business.”

“The reality is that many global supply chains were totally unprepared for Covid-19,” says Anthony Nuzio, CEO and founder of ICC Logistics.” For years now, industry leaders have been warning companies to be prepared for supply chain disruptions.”

A corporation also needs critical information from outside the chain, including checking available financial data on suppliers to ensure they are stable enterprises. That involves but checking public records if available to see whether they are solvent and have sufficient liquidity. Information on port delays and freight carriers—including trucks, ships, planes, and trains—can alert a business to slowdowns.

A company should also monitor reports of potential disruptions, whether global contagion, natural disasters, or geopolitical upheaval, and how they might affect production of products, components, or materials that a company needs to manufacturer or to sell.

The urgent point is to develop the ability to anticipate when and where disruptions will happen and take appropriate steps to keep a business running.

Unfortunately, gathering information and keeping ahead of problems is exactly not what happens. Preparation requires information, and most companies don’t have visibility into their full supply chains. The result is doing business on a bet that everything will be fine.

“The inventory policy and how they’re implemented—that’s the first fatal flaw in the system,” Alpeter says. For years, experts of all sorts told executives that if they held less inventory, it made the balance sheet look stronger. They likely said more, but at too many companies, that’s all that stuck. “If you’re optimizing to minimize risk, you likely get a different outcome than if you’re optimizing for a balance sheet.” The balance sheet choice is fine until the supply chain isn’t because there hasn’t been the monitoring and adjustments to reduce the impact of a disruption, as the pandemic has shown.

Over concentration in markets

One strategy to keep supply chains flexible and capable of managing disruption is supplier diversity, both in the number of sources of any given product and geographic location.

Corporate approaches have been largely out of sync in three ways. One is that in many industries, consolidation among companies reduces the number of potential vendors. Two, companies try to reduce the number of vendors they work with to gain importance and improved terms as they become bigger customers of their business partners as well as to simplify vendor management.

Third, in some markets, a few suppliers can become dominant or at least significant, like the factories in Japan that were major suppliers of resins and cleaning solvents used in semiconductor and printed circuit board manufacturing. When the tsunami hit in 2011, those plants were shut down, leaving the industries they served unable to get the volumes of materials they needed.

“I think the consolidation is such a big piece of it, especially for larger companies that focus to consolidate things, streamline them,” says Carlos Castelán, managing director of The Navio Group. “They can typically move really fast and cost-effectively when there are limited issues. But when something happens, it ripples throughout the supply chain. There are sometimes options, but it’s going to take more time. We’re talking months of time where you have to go find a new vendor.” Having existing alternatives reduces the delay.

Sub-optimization

The third major factor is sub-optimization, a term that was popular in the 1990s when consultants explained operational weaknesses within companies. Rather than directing all the parts of a company to achieve a common goal and shared measures of success for compensation, siloed divisions focused on departmental goals, potentially throwing the whole operation out of kilter because the compensation drove behavior focused on the success of the silo, not the company as a whole.

It is like a car where, to ensure the best performance of brakes, that part of engineering would design them to lock tight and never release. The result is absolute cessation of movement. Of course, that undercuts the point of the automobile.

As difficult as this is to control within a single organization, it becomes exponentially harder when companies must work together to enable a supply chain. One example is in the backup of ports in California.

“People think it’s a lack of truck drivers, but that’s not even close to the issue,” says Caitlin Murphy, CEO of Global Gateway Logistics, which is a freight forwarder. “The congestion at U.S. ports is complex because there are so many issues at play.” One is a lack of gate hours. “You have all this bottle-necked freight, and the drivers line up all day long to get their freight. If it’s 6 p.m. and there are still 35 drivers trying to get containers, the port tells the drivers come back tomorrow.” There aren’t enough people available to process paperwork and release contents to drivers because “the amount of customer service they have to do every day has quadrupled.”

Another issue is the handling of containers. “An empty container would come into LA,” Murphy says of the past. “A lot of times it would go inland on rail.” A company would receive it, fill the container, and send it back, the process taking about a month, at which point there’d be a vessel to take it to another country.

“Now what you’re seeing is the steamship lines are making hand over fist in various lanes, especially Asia Pacific,” Murphy says. The steamship lines route empty containers to ship immediately to China and pick up content at extremely high rates.

Companies in the Midwest now must unload cargo at the ports from containers to trucks and also send products in trucks to ports. The additional load makes a shambles of scheduling, with no no cohesive system to match trucks and containers. “Unless the steamship line is part of the solution by allowing empty containers back to the Midwest, we will never resolve this problem,” she adds.

An international problem

The supply chain might improve if conditions allow, but that will only mean the problems recede into the shadows—until some other situation again sets everything upside down.

Executives can take steps within their own companies by instituting the types of changes experts have suggested: using technology and data to monitor their supply chains, looking for advanced signs of trouble, and then taking appropriate action.

That doesn’t solve all the problems by any means. But it would give companies a fighting chance to make smarter choices, keep total operations as efficient as possible, and find solutions for problems before entire supply chains get bogged down.

Source: Published without changes from Zenger News